As we approach July 20th and the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing on the Moon, the focus will naturally be on the astronauts and their journey. Yet we should also recall that the lunar landing may not have happened save for a brief speech on a warm September day a long time ago.

It might be surprising to Americans today, accustomed to media sound bites, “fake news,” and general unfamiliarity with the art of oratory, that a speech can persuade minds and even turn the course of history. It has the power to reshape attitudes and behaviors. A great speech, like a great book or film, makes you ponder and reflect long after you have absorbed it.

Most of the great orations of the past exist today as transcriptions, sometimes quite inaccurate in their recording. The actual words of Pericles and Mark Antony are lost to history; we hope that medieval copyists give us their essence if not their original flavor. Even in the modern era, a speech that comes to us in print may not be the one that was actually delivered. The oft-cited example of the Gettysburg Address demonstrates how the text can be misremembered or misrecorded and in most cases cannot capture the diction, cadence, and manner of the speaker.

The first voice recording we have of a president is a fragment of Benjamin Harrison speaking about the first Pan-American Congress in 1889;1 it is barely enough, but sufficient to suggest what the elocution of a late 19th-century orator sounded like. A few other early recordings of 19th-century public figures such as William Jennings Bryan and P.T. Barnum impress upon a listener how public speech in the Victorian era compares to the efforts of our contemporary practitioners, those loquacious beneficiaries of content-optional high-definition video and surround sound.

Yet it was a gradual descent into our current mediagenic morass where anyone with something to say can act the amateur journalist, policy maven, or podcaster. Although TV and video technology advanced rapidly in the 1950s, it took a while for public figures to become aware (and consequently self-aware) that they could adopt the affectations of film stars and dictators to enthrall the home audience and still give a coherent speech. Thus the film and TV appearances of public figures in the late 1950s and early 1960s have a verisimilitude that is seldom found in our century; they preserve a momentary balance of form and content before the medium engulfed the message.

My exemplar here is President Kennedy’s speech at Rice University on September 12, 1962. This is the now-famous “Moon” speech that JFK delivered before an audience of 40,000 gathered in Rice Stadium.2 The rhetorical power of his remarks still resonates today and can be compared favorably with speeches by any of his successors. For those of us too young to recall Kennedy or the Apollo missions, it’s remarkable that, through technology, we can still appreciate this 18-minute speech and the achievements that followed from it.

Notes:

1 Thomas Edison wrote in his diary that he demonstrated the first version of his recording phonograph for Rutherford Hayes at the White House in April 1878. Unfortunately, no surviving recording of the president’s voice has ever been discovered.

2 This is the original video as partially restored by NASA, and you will see about halfway through the video, the quality improves dramatically. The figure just behind the president (wearing sunglasses) is Vice President Johnson, the chair of the National Aeronautics and Space Council and the primary force behind Project Apollo. Also, note that the Venus space probe referred to by the president is Mariner 2, which in December 1962 became the first spacecraft to reach another planet.

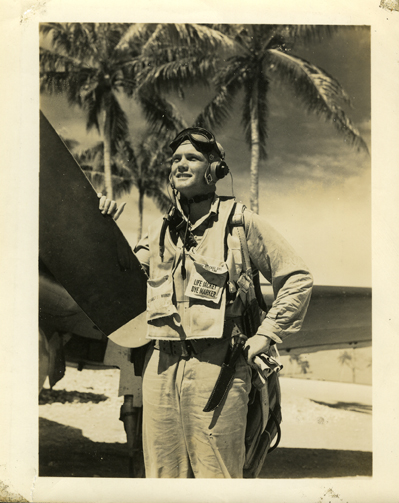

Photo credit: Robert Knudsen. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

You must be logged in to post a comment.